Public Health and Pandemics in Ontario

Public Health and Pandemics in Ontario

Discover some of the measures municipalities used to take in the 19th century to combat common communicable diseases.

By Liz Dommasch, County Archivist

During the COVID-19 pandemic, steps to ensure public health and safety were implemented to ensure that the virus didn’t spread. Such preventive measures included physical or social distancing, quarantining, proper ventilation, hand washing, and personal protective equipment (ie. Face masks). Many of these measures are not new for combating commutable diseases in Canada, and many can be traced back to the 1800s. Municipalities responsible for ensuring public welfare, enacted rules and regulations, such as the following, to ensure their communities stayed healthy:

Rules and Regulations for the preservation of Public Health in the Township of East Zorra

(as outlined in By-law No. 304 dated 1885)

Rule 1: All putrid and decaying animals or vegetable matter must be removed from all cellars, buildings, out buildings and yards on or before the 15th day of May in each year.

Rule 2: Every householder and every hotel and every restaurant keeper or other person accumulating garbage shall have proper covered receptacle for swill and house offal, the contents which shall between the 15th day of May and the 1st day of November be regularly removed as often as twice a week.

Rule 3: No animals affected with any infectious or contagious disease shall be brought or kept within this Municipality except by permission of the board.

Rule 4: No person shall offer for sale as food within this Municipality any diseased animal or any meat, fish, fruit, vegetables, milk or other articles of food which by reason of disease, decay, adulteration, impurity or any other cause shall be unfit for use.

Rule 5: The keeper of every livery or other stable shall keep his stable and stable yard clean and shall not permit between the 15th day of May and the 1st day of November more than two wagon loads of manure to accumulate in or near the same at any time except by permission of the Board of Health.

Rule 6: Any householder in whose dwelling there shall occur a case of scarlet fever, diphtheria, smallpox, cholera, typhus or typhoid fever or other disease dangerous to public health shall immediately notify the Board of Health of the same and until instructions are received from the board shall not permit any clothing or other property to be removed from his house nor shall any occupant of the said house change his or her residence to any other place within the Municipality without the consent of the board.

Rule 7: Whenever there shall come under the observation of any physician a case of cholera, scarlet fever, typhus fever or typhoid fever, diphtheria, smallpox or other disease dangerous to public health be shall at once report the same to the Medical Health Officer.

Rule 8: No person sick with any of the diseases specified in Rule 6 shall be removed at any time except by permission and under direction of the Board of Health.

Rule 9: Each and every person affected with any of the diseases specified in Rule 6 shall be immediately separated from all persons liable to contract or communicate the disease and no one having had access to any person so affected shall mingle with the general public except such person is an attending physician or clergyman who shall be required to adopt all needful precautions to the spread of such disease. Nothing shall be permitted to pass from the person so affected to any outside person unless the same shall first have been properly disinfected.

Rule 10: Persons recovering from any of the diseases specified in Rule 6 and nurses who have been in attendance or any person suffering from any such disease shall not leave the premises till they have received from the attending physician that in his opinion they have taken such precautions as to their persons clothing and all other things they proposed bringing from the premises as are necessary to ensure the immunity from infection of other persons with whom they may come in contact.

Rule 11: All persons named in the last preceding Rule are required to adopt for the disinfection and disposal of excreta and for the disinfection of utensils, bedding, clothing and other things which have been exposed to infection such measures as have been or may hereafter be advised by the Provincial Board of Health or by the Medical Health Officer or such as may have been recommended by the attending physician as equally efficacious.

Rule 12: No person suffering from or having very recently recovered from smallpox, diphtheria, scarlet fever, typhus fever, measles, whooping cough, shall expose himself in any conveyance in this Municipality without having previously notified the owner or person in charge of such conveyance of the fact of his having or having recently had such disease.

Rule 13: The owner or person in charge of any such conveyance must not after the entry of any infectious person into his conveyance allow any other person to enter it without having sufficiently disinfected it under the direction of the Board of Health or the supervision of the Sanitary Inspector or Medical Health Officer.

Rule 14: No person shall transmit, sell, or expose to, from or within this Municipality any bedding, clothing or other article likely to convey any of the diseases named in Rule 6 without having first taken such precautions as the board may direct as necessary for removing all danger of communicating any such disease to others.

Rule 15: No person shall let or hire any house or room in a house in this Municipality in which house any the said diseases have recently existed without having caused such house and premises used in connection therewith to be disinfected to the satisfaction of the health officers or authorities.

Such regulations were common to combat the number of pandemics that occurred during the 1800s. For example, between 1832 and 1854, Canada experienced at least five major outbreaks of cholera. The first outbreak in 1832, began in Quebec with the arrival of crowded immigrant ships from Europe that brought the disease with them. Although quarantine stations were set up upon arrival in Quebec, the disease quickly spread across Lower and Upper Canada. When the first pandemic finally ended, it had killed close to 6,000 people including Charles Ingersoll, the son of Major Thomas Ingersoll and brother of James Ingersoll, Oxford’s first Registrar. Charles, an elected member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada for Oxford County in 1824 and 1830, was still in office at the time of his death.

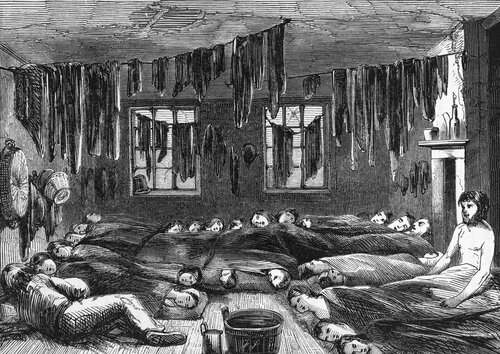

1850 engraving depicting cramped and squalid housing conditions in London. Credit: Wellcome Images via https://www.tfcg.ca/history-of-cholera-canada

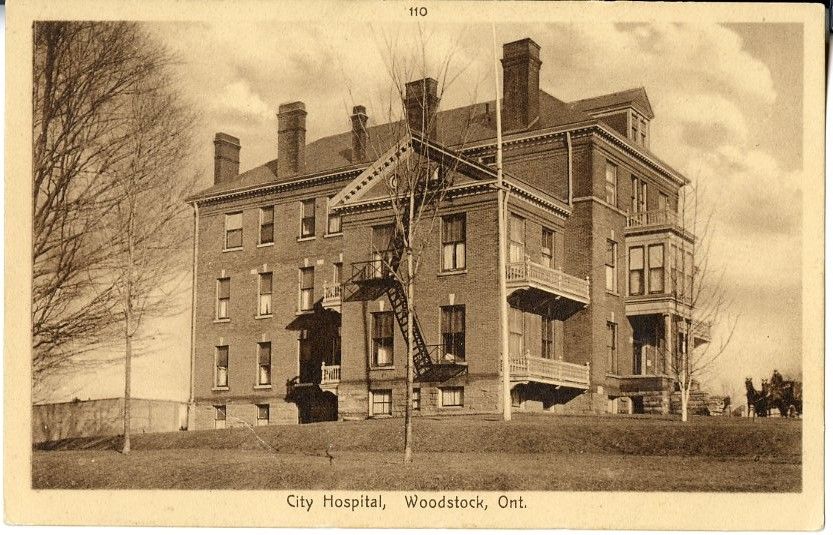

In 1847, over 9,000 immigrants from the British Isles, particularly those of Irish descent, died of typhus during the Atlantic crossing while another 10,037 died at the quarantine station of Grosse-Ile, or in the hospitals of Quebec, Montreal, Kingston and Toronto. Conditions were made worse, with people flocking to urban centres and living in squalid conditions with no plumbing, poor ventilation, and contaminated drinking water, which caused infectious diseases to flourish. The typhus epidemic was so bad that year that it was actually dubbed “the year of the typhus”. Fear and panic ran rampant across the Province and Irish immigrants were often turned away from lodging or work for fear of the disease spreading. In the 1880s, frequent typhoid fever epidemics actually spurred the town of Woodstock to improve its water supply and eventually establish the first hospital.

Woodstock City Hospital in the early 1900s [COA PC 17].

A portion of a report to the Mayor and the Council of the Town of Woodstock from Wm. M. Davis, Town Engineer re. an outlet for the Dundas Street West sewer, the construction of a sewer for the drainage of the area now drained by the Cattle Drain, and the drainage of the closed ponds. – 28 April 1890.

Prior to the 1880s, many common infectious diseases were thought to be due to bad air or heredity. However, with the emerging discipline of bacteriology and the discovery of the pathogenic agents of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, cholera, and diphtheria; popular theories of the nature of infectious diseases began to change. In fact, the knowledge about how infectious diseases were spread brought the realization that individuals and communities could do something to prevent the spread of disease through actions related to hygiene, sanitation, sewer systems, restrictions on livestock, and vaccination.

In 1882, Ontario became the first provincial government to establish a full-time Provincial Board of Health and two years later, the province strengthened its public health act by requiring that a local board of health is established in each city, village, and township. In Oxford County, Boards of Health and Sanitary Inspectors were put in place to help promote and protect public health in each community. In 1878, the Township of West Zorra passed a by-law delegating their powers as Health Officers to a committee in order to properly look after the sick following the spread of smallpox within the municipality.

In 1912, the Act was amended again so that health units could be established on a County basis.

By-law No. 304 of the Township of East Zorra re. role of the Board of Health, including Rules

and Regulations for the preservation of public health. – 30 March 1885.